The long-tailed weasel, also known as the bridled weasel, masked ermine, or big stoat, is a species of weasel found in North, Central, and South America. It is distinct from the short-tailed weasel, also known as a "stoat", a close relation in the genus Mustela that originated in Eurasia and crossed into North America some half million years ago; the two species are visually similar, having long, slender bodies and tails with short legs and a black tail tip.

📌 Taxonomy

The long-tailed weasel was originally described in the genus Mustela with the name Mustela frenata by Hinrich Lichtenstein in 1831. In 1993, the classification, Mustela frenata, was accepted into the second edition of the Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference, which was published by the Smithsonian Institution Press.

📌 Evolution

(bottom right), as illustrated in Merriam's Synopsis of the Weasels of North America]]

The long-tailed weasel is the product of a process begun 5–7 million years ago, when northern forests were replaced by open grassland, thus prompting an explosive evolution of small, burrowing rodents. The long-tailed weasel's ancestors were larger than the current form, and underwent a reduction in size to exploit the new food source. The long-tailed weasel arose in North America 2 million years ago, shortly before the stoat evolved as its mirror image in Eurasia. The species thrived during the Ice Age, as its small size and long body allowed it to easily operate beneath snow, as well as hunt in burrows. The evolution of an elongated body shape maximizes the efficiency with which Mustela frenata can trap prey underground, as the majority of it lives in burrows and in tunnels. The long-tailed weasel and the stoat remained separated until half a million years ago, when falling sea levels exposed the Bering land bridge, thus allowing the stoat to cross into North America. However, unlike the latter species, the long-tailed weasel never crossed the land bridge, and did not spread into Eurasia.

📌 Habitat size and distribution

The home range of the long-tailed weasel is estimated to range between 10-20 ha (25-50 ac) with densities of 1 weasel/km² (2.6/mi²), with the maximum number of weasels being 7 weasel/km² (18/m²). Long-tailed weasels are solitary in nature and prefer distance between themselves and members of their own species.

📌 Identification

===Tracks and scat===

The footprint of a long-tailed weasel is about 1 inch (25 mm) long. Although they have five toes, only four of them can be seen in their tracks. The only exception to this is when walking in the snow or mud, all five of their toes are shown. Their footprints will also appear heavier if the weasel is carrying food. Another way to determine the presence of a weasel is by looking for wavy indents made by their tails in the snow.

The long-tailed weasel uses one spot to leave their feces. This spot is usually near where they burrow. They'll continuously use this spot for their droppings until it gets covered by environmental changes.

📌 Distinguishing features

, Washington.]]

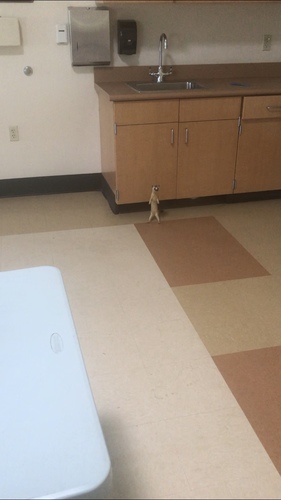

A black-tipped tail, yellowish-white belly fur, and brown fur on its back and sides are distinguishing for the long-tailed weasel. Additionally, the long-tailed weasel has long whiskers, a long narrow body, short legs, and a long tail that is approximately half the length of the body and head of the weasel. The long-tailed weasel has a triangular-shaped head, which is accentuated by small, round ears towards the back of the head. Males can be up to double the weight of females due to the size of the skull. Female long-tailed weasels have narrower skulls, which allows for more efficient hunting within the burrows of their rodent prey. Compared to the short-tailed weasel the long-tailed weasel lacks a white line on the insides of its legs.

📌 Behaviour

===Reproduction and development===

The long-tailed weasel mates in July–August, with implantation of the fertilised egg on the uterine wall being delayed until about March. The gestation period lasts 10 months, with actual embryonic development taking place only during the last four weeks of this period, an adaptation to timing births for spring, when small mammals are abundant. Litter size generally consists of 5–8 kits, which are born in April–May. The kits are born partially naked, blind and weighing , about the same weight of a hummingbird. The long-tailed weasel's growth rate is rapid, as by the age of three weeks, the kits are well furred, can crawl outside the nest and eat meat. At this time, the kits weigh . At five weeks of age, the kits' eyes open, and the young become physically active and vocal. Weaning begins at this stage, with the kits emerging from the nest and accompanying the mother in hunting trips a week later. The kits are fully grown by autumn, at which time the family disbands. The females are able to breed at 3–4 months of age, while males become sexually mature at 15–18 months.

📌 Denning and sheltering behaviour

The long-tailed weasel dens in ground burrows, under stumps or beneath rock piles. It usually does not dig its own burrows, but commonly uses abandoned chipmunk, ground squirrel, gopher, mole, and mountain beaver holes.

📌 Defense

The enemies of the long-tailed weasel are usually coyotes, foxes, wildcats, wolves, and the Canadian lynx. The weasel will give off its musky odor, however, this is not primarily used when encountering other creatures. When leaving an area they were just in, they will leave their odor behind. This is done by the weasels taking themselves and hauling their bodies across surfaces they just interacted with. The long-tailed weasel does this to "discourage predators" from coming back to the area, possibly indicating that the weasel considers this a safe haven for return. Tree-climbing is another type of defense mechanism that long-tailed weasels utilize against predators on the ground. When the long-tailed weasel becomes more white in the winter, this defense mechanism is especially used. The black-tipped tail distracts predators from the rest of the body, as it is more visible to the eye of a predator. This causes the visibility of the actual weasel to be rather difficult and makes the predator attack the tail instead of the weasel. The weasel is allowed to escape the predator because of this.

📌 Subspecies

, 42 subspecies are recognised.

{| class="wikitable collapsible collapsed" style="width:80%;"

|- style="background:#115a6c;"

!Subspecies

!Trinomial authority

!Description

!Range

!Synonyms

|-

|Bridled weaselN. f. frenata

(Nominate subspecies)

|Lichtenstein, 1831

|A large subspecies with a long tail, relatively short black tip and has a black head with conspicuous white markings

|Mexico

|aequatorialis (Coues, 1877)

brasiliensis (Sevastianoff, 1813)

mexicanus (Coues, 1877)

|-

|N. f. affinis

|Gray, 1874

|A large, very dark subspecies with very little white marking on the face

|

|costaricensis (J. A. Allen, 1916)

macrurus (J. A. Allen, 1912)

meridana (Hollister, 1914)

|-

|N. f. agilis

|Tschudi, 1844

|

|

|macrura (J. A. Allen 1916)

|-

|Black Hills long-tailed weaselN. f. alleni

|Merriam, 1896

|Similar to arizonensis in size and general characters, but with yellower upper parts

|The Black Hills, South Dakota

|

|-

|N. f. altifrontalis

|Hall, 1936

|

|

|saturata (Miller, 1912)

|-

|Arizona long-tailed weaselN. f. arizonensis

|Mearns, 1891

|Similar to longicauda, but smaller in size

|The Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountain systems, reaching British Columbia in the Rocky Mountain region

|

|-

|N. f. arthuri

|Hall, 1927

|

|

|

|-

|N. f. aureoventris

|Gray, 1864

|

|

|affinis (Lönnberg, 1913)

jelskii (Taczanowski, 1881)

macrura (Taczanowski, 1874)

|-

|Bolivian long-tailed weaselN. f. boliviensis

|Hall, 1938

|

|

|

|-

|N. f. celenda

|Hall, 1944

|

|

|

|-

|Costa Rican long-tailed weaselN. f. costaricensis

|Goldman, 1912

|

|

|brasiliensis (Gray, 1874)

|-

|N. f. effera

|Hall, 1936

|

|

|

|-

|Chiapas long-tailed weaselN. f. goldmani

|Merriam, 1896

|Similar to frenata in size and general characters, but with a longer tail and hind feet, darker fur and more restricted white markings

|The mountains of southeastern Chiapas

|

|-

|N. f. gracilis

|Brown, 1908

|

|

|

|-

|N. f. helleri

|Hall, 1935

|

|

|

|-

|Inyo long-tailed weaselN. f. inyoensis

|Hall, 1936

|

|

|

|-

|N. f. latirostra

|Hall, 1896

|

|

|arizonensis (Grinnell and Swarth, 1913)

|-

|N. f. leucoparia

|Merriam, 1896

|Similar to frenata, but slightly larger and with more extensive white markings

|

|

|-

|Common long-tailed weaselN. f. longicauda

|Bonaparte, 1838

|A large subspecies with a very long tail with a short black tip. The upper parts are pale yellowish brown or pale raw amber brown, while the underparts vary in colour from strong buffy yellow to ochraceous orange.

|The Great Plains from Kansas northward

|

|-

|N. f. macrophonius

|Elliot, 1905

|

|

|

|-

|Redwood weaselN. f. munda

|Bangs, 1899

|

|

|

|-

|New Mexico long-tailed weaselN. f. neomexicanus

|Barber and Cockerell, 1898

|

|

|

|-

|Nevada long-tailed weaselN. f. nevadensis

|Hall, 1936

|

|

|longicauda (Coues, 1891)

|-

|Nicaraguan long-tailed weaselN. f. nicaraguae

|J. A. Allen, 1916

|

|

|

|-

|N. f. nigriauris

|Hall, 1936

|

|

|xanthogenys (Gray, 1874)

|-

|

N. f. notius

|Bangs, 1899

|

|

|

|-

|New York long-tailed weaselN. f. noveboracensis

|Emmons, 1840

|A large subspecies, with a shorter tail than longicauda. The upper parts are rich, dark chocolate brown, while the underparts and upper lip are white and washed with yellowish colouring.

|The eastern United States from southern Maine to North Carolina and west to Illinois

|fusca (DeKay, 1842)

richardsonii (Baird, 1858)

|-

|N. f. occisor

|Bangs, 1899

|

|

|

|-

|N. f. olivacea

|Howell, 1913

|

|

|

|-

|Oregon long-tailed weaselN. f. oregonensis

|Merriam, 1896

|Similar to xanthogenys, but larger, darker in colour and with more restricted facial markings

|The Rogue River Valley, Oregon

|

|-

|N. f. oribasus

|Bangs, 1899

|

|

|

|-

|Panama long-tailed weaselN. f. panamensis

|Hall, 1932

|

|

|

|-

|Florida long-tailed weaselN. f. peninsulae

|Rhoads, 1894

|Equal in size to noveboracensis, but with a skull more similar to that of longicauda. The upper parts are dull chocolate brown, while the underparts are yellowish.

|Peninsular Florida

|

|-

|N. f. perda

|Merriam, 1902

|

|

|

|-

|N. f. perotae

|Hall, 1936

|

|

|

|-

|N. f. primulina

|Jackson, 1913

|

|

|

|-

|N. f. pulchra

|Hall, 1936

|

|

|

|-

|Cascade Mountains long-tailed weaselN. f. saturata

|Merriam, 1896

|Similar to arizonensis, but larger and darker, with an ochraceous belly and distinct spots behind the corners of the mouth

|The Cascade Range

|

|-

|N. f. spadix

|Bangs, 1896

|Similar to longicauda, but much darker

|

|

|-

|Texas long-tailed weaselN. f. texensis

|Hall, 1936

|

|

|

|-

|Tropical long-tailed weaselN. f. tropicalis

|Merriam, 1896

|Similar to frenata, but much smaller and darker, with less extensive white facial markings and an orange underbelly

|The tropical coast belt of southern Mexico and Guatemala from Veracruz southward

|frenatus (Coues, 1877)

noveboracensis (DeKay, 1840)

perdus (Merriam, 1902)

richardsoni (Bonaparte, 1838)

|-

|Washington long-tailed weaselN. f. washingtoni

|Merriam, 1896

|Similar to noveboracensis in size, but with a longer tail with a shorter black tip

|Washington

|

|-

|California long-tailed weaselN. f. xanthogenys

|Gray, 1843

|A medium-sized subspecies with a long tail, a face with whitish markings and ochraceous underparts

|The Sonoran and transition faunas of California, on both sides of the Sierra Nevada Mountains

|

|}

📌 Cultural meanings

In North America, Native Americans (in the region of Chatham County, North Carolina) deemed the long-tailed weasel to be a bad sign; crossing its path meant a "speedy death".